We met in Union Bridge with our hostesses utilizing a Valentine’s theme, floral design courtesy of Carmen. Our February program was given by Sue Christensen and walked us through a broad overview of how Americans utilized their outdoor spaces and covered the philosophies behind landscape design.

We saw how even the Pilgrims came with ideas for laying out their utilitarian garden spaces. The prototype originally came from the mathematically precise layouts popularized in France, as seen in the King’s gardens at Versailles copied in other countries like Britain.

While American colonists clung to the familiar, while fighting against and taming the wilderness, England began to develop a new style that rebelled again the old walled estate and symmetrical parterre French gardens. Primarily utilized by the English aristocracy, this was the romantic period English Landscape Style which is associated with Lancelot Capability Brown. Vast expanses of grassland, clumps and belts of trees, serpentine streams were built in though massive landscaping efforts, make a garden-less view of the estate acreage, modeled after romantic painting of the time. There might be additions of bridge works or follies as well.

Our American kneaders wanted to avoid ostentation excess, and did not want to encourage this aristocratic style. They were more for practicality and simplify. Having the same types of gardens across social strata was considered a way of showing that all were created equal. So, Americans stuck with the symmetry of the classic style.

We looked at how Jefferson viewed farming and country life as superior to and more virtuous than life in the city and mercantile interests. He was responsible for adding more lands to encourage farming in the Louisiana Purchase and for the plant collecting of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

We saw the impact of immigration on many aspects of American life. In Baltimore, for example, the B&O railroad made deals with with shipping lines to bring in German and Eastern European immigrants who would be sent on to populate new lands in the west as yeoman farmers. Likewise, the railroad industry supported growth of other industries and drew in Irish workmen for laborious jobs. As more farmers began to grow crops in the west, prices dropped for city dwellers who could afford to spend more of their dollars on other types of goods, so standards of living rose. However, inventions and increase of competing crops dropped prices for farmers who were not able to stay afloat, mired in debt. Many would end up leaving farm life to fuel the labor force in the growing cities.

The more people flowed to the cities, the more noxious and crowded conditions became. Upper classes began to fear for their safety with rising theft and riots occurring frequently plus the masses of stinking humanity and industrial pollution on their very doorsteps. The wealthiest began to look to escape at least to country homes. This is where the English landscape style began to take root in the US through the rockstar personage of Andrew Jackson Downing who wrote “A Treatise on the Theory and Practice on of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America”. The romantic style idealized natural scenery. Downing felt that one of the finer things a man of wealth and taste could do was landscape his country property to uplift raw nature. He incorporated the Picturesque, i.e. irregular plantings that are abrupt, wild and bold as a transition to surrounding nature and the “Beautiful” associated with luxuriant, symmetrical flowing foliage near the house. He promoted these gardens as suitable alongside the Gothic Revival style of architecture. His designs were eagerly sought by upper classes in US.

We also investigated Victorian family values and women’s roles in gardening, especially flower gardening around the house. The male arena was exterior to the home– urban affairs and the public sphere, whereas women were moral guardians of family and home, meant to inculcate the American Republican-Protestant values to children and provide a haven for their husbands as “Angels of the House”. With surges in immigration, household help was cheap, so many women relied on servants. In flower gardens, proper sphere for Victorian ladies, they were only to do fine light garden work; digging in the dirt was a lower class occupation. Many Englishwomen assessed American women as weak and hot-housed, mere dilettantes. As women’s suffrage became a factor, many women who felt stifled in their proscribed roles took on the challenges of city squalor, education and promotion of health in urban areas by promoting parks for all classes and vegetable and flower gardening by immigrant groups.

A protege of Downing, Frederick Law Olmstead, Sr. also embraced the Romantic landscape style and held a strong belief in the curative, uplifting powers of exposure to nature. He felt that all classes had a right to access common greenspace; He designed New York Central Park utilizing picturesque and pastoral ideals. Olmstead also designed picturesque suburbs that were accessible by horse and streetcars, on irregular lots and scenic drives. He believed that one should endeavor to work with the genius of a site, follow the topography and avoid straight lines. There was an emphasis on setbacks and expanses of lawn that allowed the expression of living in a park like setting.

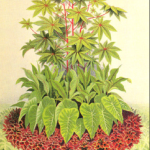

Carpet bedding, the earlier Victorian style, was a very expensive one that relied on setting out thousands of plants grown in greenhouses–especially the brightly colored new annuals and tender perennials. Patterns were drawn in colored sand on prepared areas in all manner of geometric shapes, then planted in a tapestry style reminiscent of Oriental rugs. They would be planted out for a few weeks, then discarded and replaced three to four times. This would cost a princely sum, scarcely affordable by any but the richest persons. This carpet bedding was a grower’s art–referred to as “Gardenesque”.

The later Victorian period, evinced by the Queen Anne architecture began to tone down the colors used in the bedding schemes and introduce more perennials. Showcasing specimens and collections was very popular as were conservatories and container plants on porches. Circle bedding, viewable from parlor windows, was typical. Many people used their yards and gardens as outdoor living spaces for dining, strolling, playing lawn games and conversation. Often in warmer months, it was often much more comfortable to be outdoors than inside.

As more immigration occurred from countries with Catholic, Jewish and Eastern Europeans, nativism gripped the country. There was a fear that the newcomers would overthrow the founding principles and the U.S. would become a different sort of country. With the 1876 centennial, architects began to look backwards at American styles from the colonial period. This Colonial Revival period also reawakened an interest in old style gardens called “Grandmother’s Gardens” of old floral favorites steeped in nostalgia and fragrance. Too, American native plants and hardy perennials that had been relegated to obscurity were sought out. Anything that was “American” was found to sell and was deemed patriotic. So, the more formal, geometric style utilizing boxwood lined rectangular flower beds was again in vogue as we passed into the 20th century.

- Parterre gardens and topiary in the French style

- English Landscape style

- Straight lines, geometric beds preferred by Americans

- An AJ Downing landscape style

- Roseland Cottage–Gothic Revival style

- The Angel of the House

- Women drove the City Beautiful Movement and childrens city gardens, parks.

- Curving roads in lovely Olmstead suburbia

- Overcrowded,rundown housing conditions in old urban areas

- Increase in immigration due to revolution, unrest, famine on faster ships

- Example of carpet bedding

- Streetcar lines enables the spread of suburbia

- Large porches

- Irregular rooflines of Queen Anne

- Round beds viewed from parlor

- Diane, lead hostess. Carmen, floral design

- Before the tea